Poetry and Fiction

When people talk about poets writing fiction, the common terms are often:

the beauty of language

lyrical sensibility

gorgeous

We can talk about that, if you like.

Books are shelved under cherubs representing the muses, astrological symbols, etc.

The library is a zodiac, an attempt to recreate the broken word of God.

Beautiful

*

When people talk about poets writing fiction, some common terms are:

poets shouldn’t be allowed to write fiction

poets are lazy

poets can’t develop character

poets make no sense

poets have no sense of arc

We can talk about that, if you like, but I think there is a more important context for us to discuss than what are the consequences of a misunderstanding, or split, that happened, say, three hundred years ago.

*

So, I’d like to begin with this:

Poetry and Fiction have been separated for too long, and there is too much misunderstanding between them.

It makes me sad.

*

When did the break happen? When did the happy couple divide up the silverware and the CD collection?

A long time ago, sure. But not that long. Back in medieval days, for instance, the only difference was rhyme. The prose people wrote was might darned poetic, by today’s standards.

Poetry was song, kind of. Prose was stories, kind of. But they both were what today, in the Great Destruction, we would call poetry.

They relied on inference and on elliptical connections.

*

Like, frankly, the Bible, which was real big back then and was neither one nor the other.

*

Begin again.

So, where did this fiction thing come from?

Well, out of the Enlightenment, with its ‘understanding’ and its ‘rationality’ and so forth. Out of newspapers and journalism and science and the first novels.

Novel = New.

News= New.

Aha!

To live in the moment.

Ahhhhhh! The peach blossoms on the trees!

Here follows the fictioneers version:

The woman gasping at her lover’s revelation! The consequences. The shame. The joy. The character. The heart racing. Like, oh, I dunno: Jane Austen.

A society dissected, like a frog pinned on a table.

A poem.

Dissected.

*

Hey, it’s not so far-fetched. Society was conceived of as a kind of poem.

*

Um. Yeah.

Yeah, well, fiction also came out of the baroque period, after all, which came before the Enlightenment. The baroque was big on ‘artificiality’. To the people of the period, that was a positive term. It meant ‘artifice’, it meant ‘art’, it meant ‘something that people created as an image of God.’

Not gothic God with his gloomy cathedrals, though.

No. No no no no no. Fun stuff.

Sex.

The city of Dresden laid out with the Semper Opera House by the river, like a music box, in which the people could go, to listen to the music.

Cute, huh!

In the Foreground August der Starke on his Big Horse

On the roof were Dionysus and Artemis, who had just come out of the river, the Elbe, at the back of the Opera House, and were following the king, August the Strong, on his bronze horse, into town, following him, because he had given the city the opera house, for the delight of its people, and because the river was, after all, one of the four rivers of the underworld which fertilized this world and brought it to life.

complete with Chinese Tea House (featured) and Sphinxes, flanking the landing platform.

On the river in Dresden, you could board a little junk, with a busty mermaid for a prow, and visit August’s pleasure palace in Pillnitz, where August kept his mistress, and you could leave the world for a weekend, sleep with whoever and whomever, come back downriver again on Sunday evening, and start your life again, and everything that happened up there didn’t count.

It was magic.

Fun stuff like that. The world as a poem, as part of the design of the universe.

God’s language spoken by men, to honour God.

Aww.

The Jardens des Tuilleries in Versailles, laid out l ike an alchemist’s diagram, a magical matrix, the word of God, the Word that God spoke to make the world.

That was the delight.

It was also not always so metaphysical. Sometimes it was just kitschy, but that shows how pervasive the idea was among the upper classes.

So, cute.

Here’s a story about that. In the town in which my father was a boy, there is a palace. Just a wee thing of a palace, with a dozen formal rooms — a mere speck on the wall of a palace, a summer cottage out in the country, actually. It is called Schloss Favorite.

The pattern of plaster around the windows consists of pebbles which starving village children carried in baskets from the Rhine, eight kilomet res away, for a penny a basket, and which their fathers set there, so that the power of the river would fertilize the castle as well.

A lovely little jewelry box from the 17th century. Did the dowager duchess’ sister send her an ornate table decorated with inlaid cut precious and semiprecious stones? She did, indeed. So, the dowager duchess had an entire room decorated in that manner. Etc. And in the floors of one of the rooms are set: a hand of cards, various insects, etc. All looking very lifelike.

The idea was to play with illusions between reality and unreality.

The idea was to point out a bug on the floor and startle a guest, and then everyone could laugh at how lifelike it was.

You ate your food off of china painted with little meadow flowers from Saxony. Dresden china.

A society hellbent on narrative dropped bombs on it.

February 14, 1945.

It was a trial run for Hiroshima.

People trained for ten years, so that they could paint each flower exactly the same as every other one: more real than the ‘real’ flowers in the meadows along the Elbe. More real because perfect ed. The flowers in the meadows were just pale reflections of perfect world, reflected in a fallen one, but the mind, ah, the mind was pure and came from God.

Similarly, both the Semper Opera House and Schloss Favorite feature artificially-coloured plaster pillars, made to look like luxuriously coloured marble. They were preferred to real marble. People wore wigs, because that was better than hair.

In the 16th Century, peopled had passed laws as to how the peasants should dress, so it would always be clear who was a peasant and who wasn’t.

If the Semperoper is a music box, Schloss Favorite is a china cabinet. The dowager duchess wanted to show off the china that she got from her dowry in Bohemia.

By golly.

*

Any understanding of the moment at which poetry and fiction split lies right there.

Fiction took the artificiality, and adopted it to a scientific line of thinking.

And poetry, where did it go? Into the past.

Oh, it didn’t go there intentionally. Nothing like that. The poets just wanted to stand still. They wanted that trip up the river in the junk.

Hell, I want that trip up the river in the junk.

*

Begin again.

You know, it really seemed that poetry was beaten and retreated into the past, too. In the late eighteenth century, romantic poetry crawled out of a muddy beach, gasped unto dry land, grew some nice Darwinian lungs out of its Mosaic lungs, struggled up onto its stubby fins and walked around on the beaches and declaimed.

By the time Tennyson wrote “The Lady of Shallot” and Browning “The Ring and the Book” etc., the attempt of poets to reclaim the medieval sense of a unified cosmos was pretty much solidified.

Notice the Alchemical Device (Globe)

*

Medieval sense?

Indeed.

Ever see a tapestry, a Gobelins, perhaps?

There’s a narrative, but not one which would make it into fiction. It is all there simultaneously.

Pretty much any painting by the old masters does the same thing.

The idea was that a story existed, in eternity. What we had on earth was a poor reflection.

from Cappella Maggiore of Cortona Cathedral (1516, made by Guillaume de Marcillat)

Magic.

*

Witches believed the same thing.

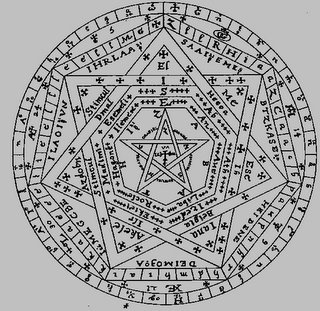

It is a function of sympathetic magic that it draws correspondences between things because of one quality, and transfers other qualities along with them.

That’s how poetry works.

*

Poets are alchemists?

Well, ya.

*

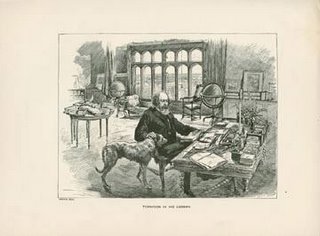

Take John Dee.

He believed that “The Book of Nature” (ie the world) was running down. The spring hadn’t, so to speak, been wound for awhile. Things started poorly in the Garden of Eden, and, since God wasn’t blowing up the beach ball, so to speak, it was getting kind of saggy.

Court Astrologer to Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth II (Not an easy trick!)

John Dee. Most learned man in Europe. Buddy to Mercator, who gave us Tennyson’s globe. In fact, Mercator gave Dee a present of one of his original globes. Taught Frobisher how to navigate. Merged science and theology. Alchemist. Spoke with angels, and wrote the conversations down.

Got into a wee spot of trouble with the Inquisition for that.

Read the world as a book, spoken by God, in a conception that led directly to the Tuilleries.

As Dictated to Him by Scientifically Apprehended Angels

That’s why fiction was created. To counter the alchemical world view. To liberate human action in an otherwise fate-bound universe.

Well, yeah.

*

Poets, however, never turned from a unified universe. Poets continued to try to find ways to accommodate scientific thinking and eternal time.

God’s time.

Poets kept up John Dee's work. They kept trying to meld inspiration with science.

Meanwhile, the fictioneers were pretty excited about their new moral, linear, time-bound universe.

I mean, why not.

They got to go up the river.

*

Linear? Time-bound?

Yes. That’s a primary difference between poetry and fiction.

Fiction works off of arcs.

Poetry works off of unities.

In fiction, action has a direction.

In poetry, action is part of a tapestry.

*

Eh?

*

Try again.

In fiction, the moment is all. The possibilities inherent in the moment are extended forward in projected time, and possible hypotheses are made as to where they will lead, and the thing that holds them together is narrative, as fiction understands it, or time.

Or the ego.

In poetry, the moment is all. The possibilities are retained as possibilities. A narrative can move from medieval London to a shopping mall in Moose Jaw, to a bird on a windowsill, to who knows where, and poets can follow that narrative.

But it is not a narrative of time.

It is a narrative of timelessness.

In fact, regarding ego, here’s what Ezra Pound, poet and modernist and medievalist and dabbler in alchemy, had to say about it, paraphrased:

In English, a verb transfers action, or dominance, from one noun to another noun, which is the object.

In Chinese, nouns and verbs exist simultaneously, as figures. They are part of a unified picture.

He got this idea by reading a manuscript called The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry, by Ernest Fenellosa.

in which he shows how a poem is made up of discrete images.

Pound was thinking of magic.

Amulets.

Charms.

Spells.

*

To put it another way: poetry embodies narratives of objects, narratives of correspondences.

Fiction embodies narratives of choice.

*

To put it another way: poetry refuses to change the nature of the world. It participates in the creation of the world, through participation in the original creation.

Prose asserts the power of the human mind to create new worlds.

*

Damn, this stuff hurts the brain.

*

Start again.

Ok, I phoned up some writers this morning. We chatted about poetry and fiction. About the fiction they wrote and the poetry they wrote. About crossing over. About coming back. Or not coming back.

About Jane Urquhart’s new novel, A Map of Glass.

We talked about how it looked like some editor screwed it up by insisting on narrative, on linear narrative, in what by all appearances started out to be a series of vignettes with elliptical connections.

And killed it.

On this point, we were all agreed.

Because the transitions that came out of the process are so unbelievably clunky. So much like Grade 9.

On this point we were all agreed, too.

Bummer.

*

Start again.

As poets this morning, and as poet-novelists, we talked about the tyranny of narrative. We talked about how narrative is bound to time, to advancing time, and has one end: death.

The following was, in a somewhat elongated form, part of the conversation:

Fictioneer: Do you see this?

Reader: Uh-huh.

Fictioneer: Well it will end!

That’s the plot that time gives us. That’s what we talked about, anyway.

*

Kind of like the Bible.

from the Book of Revelation

Kinda.

*

Poets and fictioneers have a lot to talk about. Because the only difference between the two is about whether God/Goddess or Man/Woman is at the centre of the universe.

Beyond that, there is no difference.

Sure, science measures what can be perceived and measured by rational thought, and theology measures what can be brought together, but that’s not to say that poetry and fiction still have a split in this regard.

Because some poets, like Robert Kroetsch, maintain that it’s time that poets became scientists, not alchemists, while some fiction writers are trying to become alchemists, and are discovering what the poets have known all along: the attention to the incantatory power of language is going to make the difference between pulling a spell off and not.

Which is what killed Urquhart’s novel: the insistence on a temporal and will-based narrative that did not participate in the spell, broke the spell.

*

It’s like the olympic athlete who realizes perfection of movement, perfection of arc on a ski slope, and then wakes up one morning and realizes that this body, that he spent so many years perfecting, is going to die.

I have been told it’s pretty devastating.

Well, yeah.

So, what do you do, huh?

*

The poets have a few things to say about that.

*

You see, arcs are part of circles, are part of spheres, and spheres are symbols of unity.

before Mercator Drew Continents on It

What fiction does is to separate the arcs, to play with them, to follow them, to create insects on a floor, so you can have the delight of recognition, and share that moment of correlation between the image and the world of God.

It sends shivers down your spine.

Or, at least, to your groin.

Poets understand that.

And, more than that, fictioneers delight in the personal interaction of people doing that to each other, like the Dowager duchess and her friends, having coffee and kuchen and giggling over grasshoppers painted on the floor.

Poets have had a harder time with that.

Poets thought they were already together.

They thought it was only an illusion that they weren’t.

*

What on earth were they thinking?

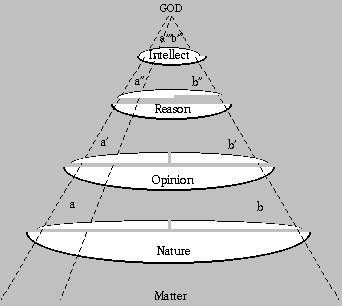

Well, the 3rd century neo-platonic philosopher Iamblichus says of the pre-classical mystery religions of the Middle East, that God was ever-present.

You could put your hand out in the light, and the hand did not break the light.

Well, not so scientific.

But that’s the point.

The pre-scientific conception of the universe, the Christian one, the Alchemical one, and, I suggest, the poetic one, is Neo-Platonic:

It’s like a chakra: different planes of spiritual energy cause the pure energy of God to be manifested in different forms. Recognition is all.

It’s like a zodiac.

Magic.

*

But, look, it all made sense when we placed the earth at the centre of the universe: everything in the sky matched everything down below, the way an image projected through a lens shows up on a screen.

It’s like Plato’s Cave

In the Copernican universe, the Sun is at the centre, though. In the Newtonian universe, there ain’t no centre.

Just an everpresent mind.

A human mind.

And what it can imagine.

*

Ain’t that the thing.

A poet doesn’t imagine stuff. Even when a poet writes a narrative, even a fictional narrative, it ain’t fiction, because it isn’t imagined, because at the centre is either the earth, or some other conception of unity.

For a poet, even fiction is truth. You make connections with correspondences, not consequences. You follow the hidden waters of the Elbe, flowing into the underworld, and back up again, anywhere.

Magic.

*

Don’t believe me? Ask Margaret Atwood, a successful poet and novelist, who claims nobody ever told her she couldn’t do both.

You can read her full talk here: http://www.web.net/owtoad/lecture.html

Look at what she says:

The day I became a poet was a sunny day of no particular ominousness. I was walking across the football field, not because I was sports-minded or had plans to smoke a cigarette behind the field house – the only other reason for going there – but because this was my normal way home from school. I was scuttling along in my usual furtive way, suspecting no ill, when a large invisible thumb descended from the sky and pressed down on the top of my head. A poem formed. It was quite a gloomy poem: the poems of the young usually are. It was a gift, this poem – a gift from an anonymous donor, and, as such, both exciting and sinister at the same time.

I suspect this is the way all poets begin writing poetry, only they don’t want to admit it, so they make up more rational explanations. But this is the true explanation, and I defy anyone to disprove it.

Magic.

*

Here’s a piece of a poem by Robin Skelton.

This

midwinter in the dark

time of the year,

give, and be thankful;

fill the house with light

to bring the light,

to bring the love, the peace

that story holds up to us

like a dream

from which we must not

ever fully wake

if years are to continue

on this earth.

*

Robin was a witch.

Robin also believed that there was ever only one story, of the goddess and her lover, and that we are all reliving that story.

That the story is timeless. It is not that time flows. We do.

*

Names

do not use too many ames,

for names

are separations,

and we all are one

in past and present;

names reverberate

particulars till the

unity is drowned

in vast obliquities

of sound and image;

rather speak of

Her without a name,

of Him without a name,

retaining thus

the rhythm of the breath:

Her Him, Her Him,

Her Him, Her Him, Her Him,

our endless music.Robin Skelton.

*

That’s the way poets and alchemists look at narrative.

*

Bookstore talk:

The German name for a novel is a “Roman”.

The German word for poetry is “Poesie”.

In German bookstores, if you go to the “Poesie” section, you will find medieval stuff, books of collected poems, inspirational quotes, that kind of stuff.

What qualifies as poetry in the popular Canadian imagination, too, as exemplified by the Poetry section in many bookstores, including, if you’re lucky, Coles.

If you go to the “Roman” section, you will find: novels.

Yeah, but not just that. You will also find: short stories, novellas, plays, poems, film scripts, and a whole host of things blending them all together.

But then, that’s a culture in which modern history begins in the 15th century.

They take the long view.

*

I wish we would, too.

*

Because the Germans have figured something out.

In a culture which is very regulated, in which most art is quoted, in which poetry is certainly quoted, in which music is reinterpreted more than it is written, in which there are so many museums, they have found a way beyond the impasse that separates genres, a way to allow for medieval senses of time to coexist with ultramodern ones, in works of fiction and poetry which erase the differences that began with the Enlightenment, and reunited what has always needed to come back together.

Cleaning Up After the Bombing of Dresden

In the Foreground: Time’s Victims

Poets can help fictioneers tell this story. I believe that we are ready for the alchemists’ time and the humanists’ time to tell the same story once again.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home